Demonstrating how to improve operational efficiency in Uganda’s overall pathology service – Part 2

Ibrahimm Mugerwa1, Tony Boova2, Van Der Westhuizen2, Christopher Okiira1, Agnes Nakakawa3, Micheal Kasusse3, Suzan Nabadda1, Gaspard Guma1, Suleiman Ikoba1, Charles Kiyaga4

1Uganda National Health Laboratory Services, 2Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, 3Makerere University, 4ASLM

Part 2 – The Detail

Uganda’s Central Public Health Laboratories (CPHL) recognized that its regional laboratory service was suffering from a number of operational and governance challenges that were affecting service delivery and patient outcomes. There were fundamental flaws in the transport management of the physical collection and transportation of samples from the rural catchment areas. In addition, the labs were affected by frequent stock out, poor equipment maintenance, lengthy downtime for instruments and slow turnaround times.

Led by the CPHL, a problem solving team was set up to identify the specific challenges and devise a workable and long-lasting solution. This focused on moving away from a centralized approach to handing responsibility for laboratory sample coordination to regional level. A pilot study was set up in Arua within the country’s West Nile Health Region because of the challenges it presented in terms of distance, existing health facilities and its high refugee population.

Between May 2016 and June 2017, CPHL funded the placement of an experienced laboratory scientist at Arua’s main referral laboratory hub to carry out the newly defined coordination tasks. This part of the paper goes into more detail about how and why the pilot was set up and the step by step processes that were carried out.

The investigators structured their decision-making in line with the Action Research approach as indicated by Susman and Evered (1978). This involved the following five stages:

- Diagnosis stage – recognizing a problem or gap in the environment

- Action planning stage –determining possible mechanisms of conducting an intervention to effectively address the problem

- Action taking stage –implementing the appropriate mechanism or action

- Evaluate stage – assessing the impact of the implemented action or mechanism

- Specify learning stage – concerned with reflecting on lessons learned to inform planning of future initiatives.

Six targets for improvement were defined as:

- Increase reliability of sample transportation mechanisms in the West Nile Health Region

- Improve laboratory inventory management at hubs

- Reduce laboratory turnaround time for all hub testing

- Strengthen working synergies for improved communication and reporting among stakeholders at all levels of the laboratory hub system in the West Nile Health Region

- Extend patient access to essential diagnostics for HIV/AIDS and opportunistic infections

- Provide cost guidelines for scaling up nationally.

Addressing complex needs of pilot study area

In January 2015, the CPHL organized a preliminary field visit to the West Nile Health Region and invited participation from the Director Alliance Development at Beckman Coulter High Burden HIV Markets. It was immediately clear that lack of on-site coordination was at the heart of the problem. Activities were being carried out on an ad hoc basis with no backup during critical staff changes. Reporting structures were not clearly defined and there were no performance targets such as test volumes, TAT and reliability requirements.

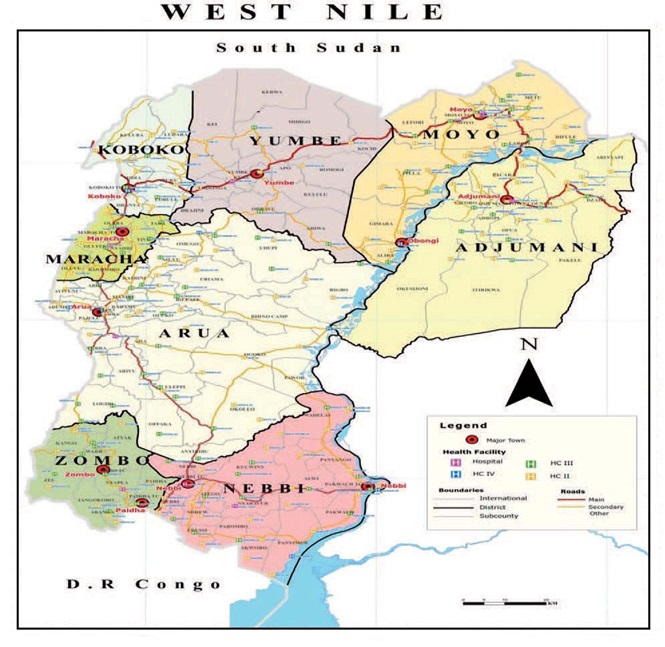

>The West Nile Health region had been initially singled out because it supported some of the most vulnerable in the country, those living in remote and hard to reach areas, with high incidence of HIV AIDS related diseases. Many were refugees from the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of South Sudan. It comprises eight districts (Figure 1) - Arua, Nebbi, Adjumani, Zombo, Maracha, Koboko, Yumbe and Moyo – each with its own laboratory hub. They in turn serve 25 to 40 lower facilities including those facilities within the humanitarian settlement sites and outreach medical camps within the refugee settlement areas.

The Arua regional laboratory hub was chosen for the pilot because of its uniquely challenged situation, serving more than 50 lower health facilities including those situated within the neighboring Maracha district, which was chosen as the control site.

Figure 1: Geographical location of these districts

Change management expertise

A three-day workshop was set up in November 2015 to identify a roadmap for change, It was attended by 20 senior laboratory scientists, laboratory logistics experts, data and information management experts, operations and human resource managers. The team included senior CPHL management, representatives from the Reference laboratories for HIV/VL, EID, microbiology and sickle cell and the National TB and Reference Laboratory.

The overall workshop was led by change management experts from Beckman Coulter Life Sciences. The first task was to understand how the regional laboratory hub system currently fitted into the overall laboratory service, so that the right mechanisms could be put in place to ensure the potential solution (of appointing a regional coordinator) would work. Kaizen tools and techniques for problem solving and strategic planning were used to define the exact problems and causes of inefficiency in the hub operations as well as quantify the magnitude of the operational limitations.

Armed with this information, a smaller task action group was then set up to carry this forward. Alongside the National HIV/VL EID Program Manager and the Head Operations at CPHL, the group involved both the Director Alliance Development at Beckman Coulter High Burden HIV Markets and a Senior Business Analyst from the parent company, Danaher Corporation. Both are experts in the Danaher Business System and its cycle of change and improvement.

To define the tactical and operational role of a regional coordination office at sub- national level, the task force first gathered information on the existing productivity levels in the eight laboratory hubs in West Nile and the sites they supported. This included:

- Turnaround time (TAT) for test results sent from the hub to requesting lower facility

- TAT from CPHL to the hub laboratory

- Volume of specimens collected at hub and then referred to CPHL.

In addition, it recorded overall hub operations and utilization of any data tools, or health facility registers, which are part of the National Health Management Information System (HMIS).

Six key performance targets (KPIs):

- Create a reliable and efficient sample transportation system

- Improve overall laboratory inventory management

- Reduce laboratory turnaround time for all tests

- Develop an ethos of collaborative working and improving communication and reporting among stakeholders at all levels of the laboratory hub system

- Increase timely access for patients to diagnostics for HIV/AIDS and opportunistic infections

- Illustrate the cost implications for implementing changes throughout the country.

Monitoring these KPIs via ongoing, quarterly reviews throughout the pilot study enabled the group to identify when further improvements were required in time for them to be successfully implemented. Two additional assessments were carried out. The first involved a comparative study of annual performance statistics for the West Nile Health Region as the pilot site and the control region, Maracha, still operating under the existing system without a regional hub coordinator. The second involved the financial implications. Key stakeholders were invited to review findings from the comparative assessment with a view to setting the framework for cost implications if this pilot was to be scaled up nationally.

Impact of improving sample transportation system

Several factors were affecting the reliability of the sample transport network such as:

- High frequency of failed routes and cycle breakdowns.

- No backup rider.

- Lack of a clearly defined and costed route schedule including no special route schedules for hubs that serve several lower facilities in hard to reach areas and in refugee settlement areas.

- No servicing and maintenance contracts for motor cycles.

- Lack of regular fuel supplies.

- No routine provision of airtime to enable the hub and lower level facilities to communicate with the sample delivery bikers, for instance about fuel deliveries.

- Lack of proper employment contracts and job security for bike riders.

Once the coordinator started to improve the service, a sharp increase in reliability was noted with route failures down by almost 98% (Figure 2) and similar efficiencies noted for bike maintenance and breakdowns.

Figure 2: Reductions in down time and failed routes for sample transportation

Fill the form to download Full case study

CD4 Testing in Remote Areas

CD4 testing in remote areas

Follow the links, to learn how Uganda designed an innovative system to ensure that people in remote communities can receive high quality HIV prevention, care and treatment services.

How Uganda is Leaving No One Behind

Around 1,350,000 people are currently living with HIV in Uganda, and there are an estimated 33 new HIV infections per day among young people between the ages of 15 and 24.

Efficient Sample Collection in Remote Areas

The main challenge faced by people in remote areas when it comes to HIV/AIDS testing is access. People in remote areas can be very poor, so it can be difficult for them to travel to the service point, although the treatment itself is free in Uganda.

High Quality Testing in Rural Communities

The majority of countries still don’t have the infrastructure, transport or technology to effectively manage the collection, storage and transportation of the blood once the sample has been taken.

Demonstrating Operational Efficiencies: Part 1

Stimulating efficiency while empowering and mentoring local laboratory professionals in workflow management underpins the remarkable improvement in the routine laboratory service of Uganda’s West Nile Health Region.

Demonstrating Operational Efficiencies: Part 2

Uganda’s Central Public Health Laboratories (CPHL) recognized that its regional laboratory service was suffering from a number of challenges that were affecting service delivery and patient outcomes.

Demonstrating Operational Efficiencies: Part 3

The initial assessment found that supplies would be delayed, with frequent stock outs, due to poor communication because there was no clear chain of command for coordinating this activity.